On Saturday, June 14, Nicky Uy of Bahay215 and I will be offering a discussion and writing workshop about connecting to ancestral plants! The workshop will take place from 3-4:30 pm, outdoors at the former Greensgrow Farm site in Philly. Sign up here 🌱

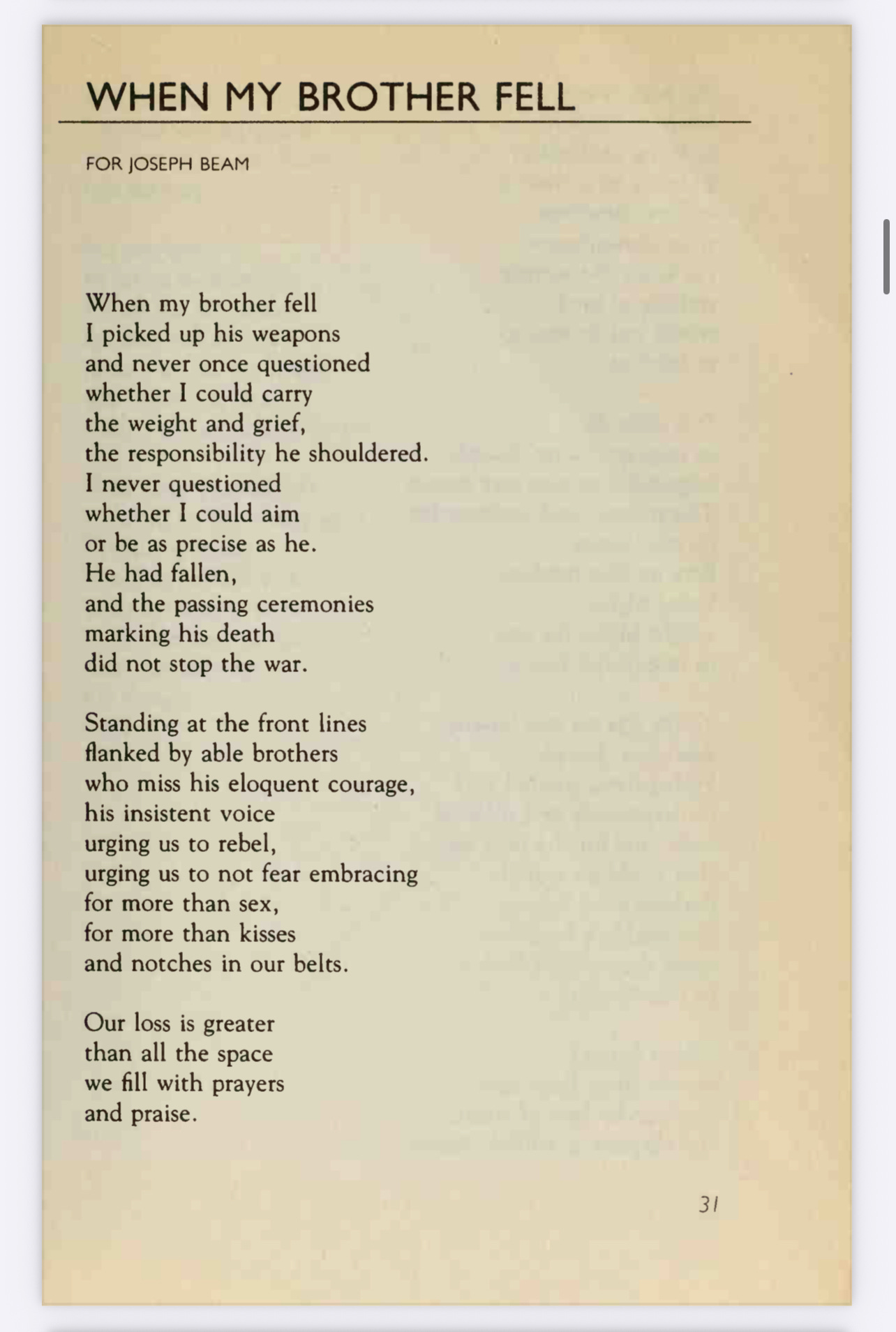

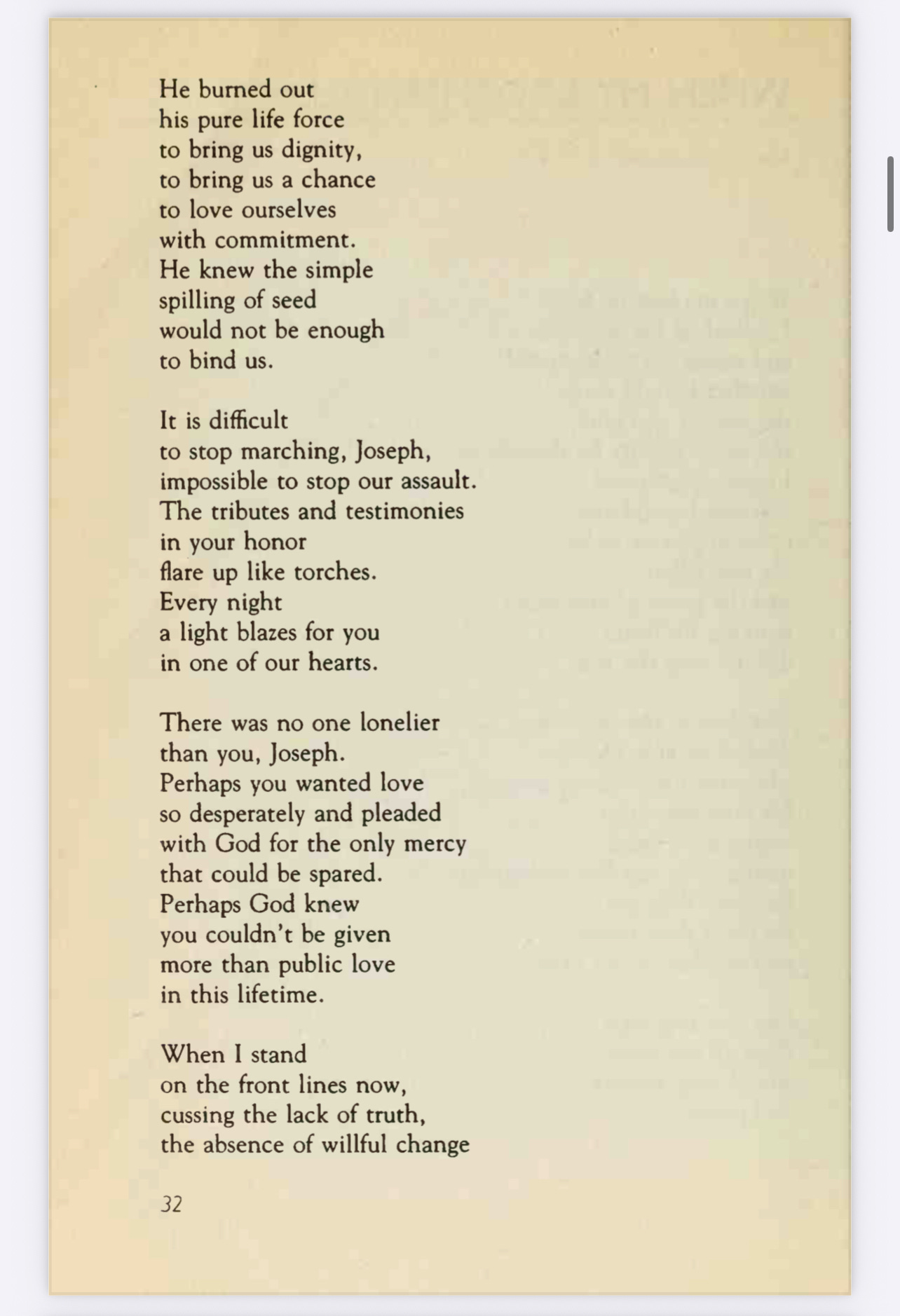

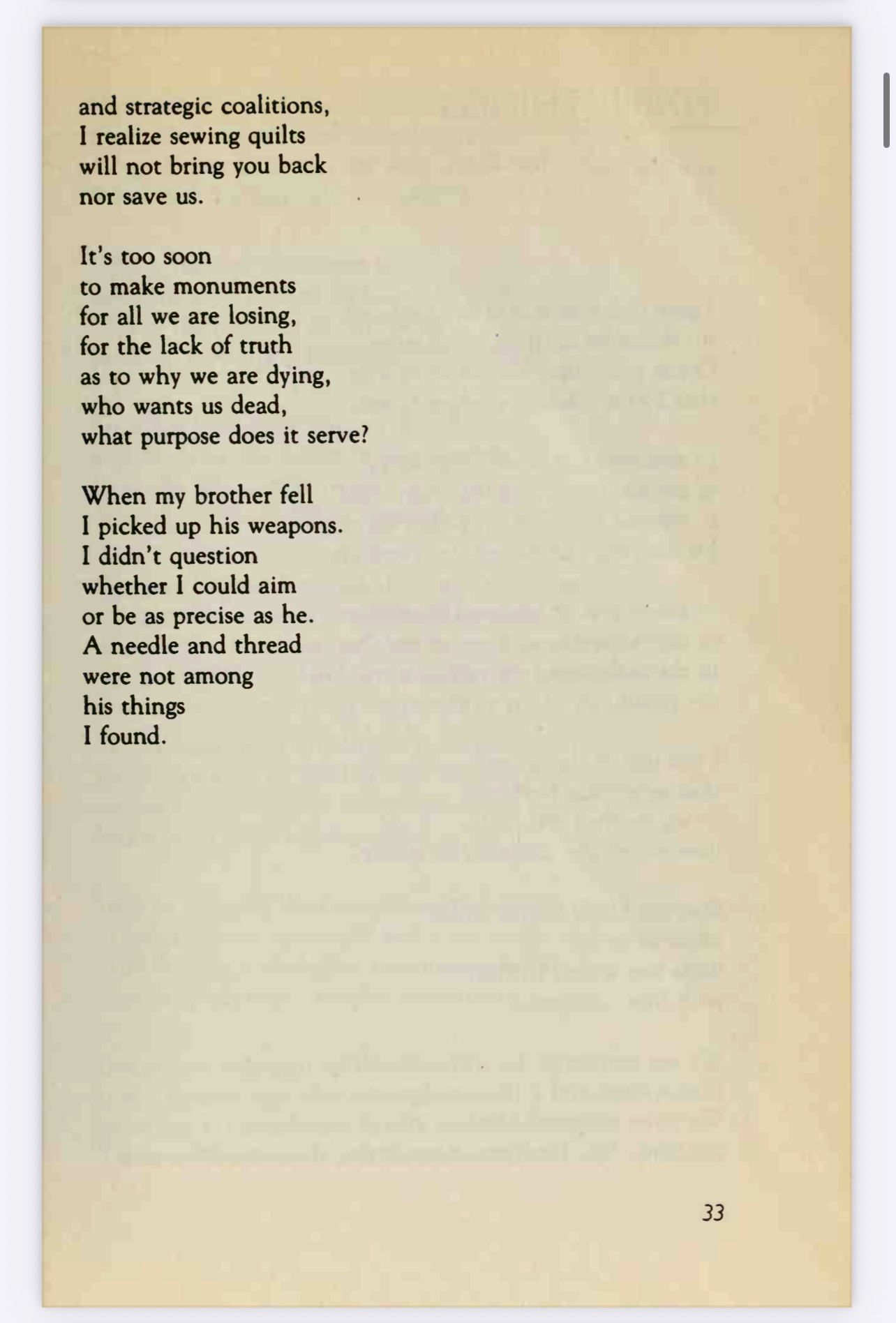

As mentioned in my last newsletter, I’ve been reading Love Is a Dangerous Word: Selected Poems by Essex Hemphill. Many of the poems in this collection were written at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the U.S., as Hemphill saw his friends falling sick around him and navigated love, desire, and political struggle in a time of mass death and government neglect. In the poem When My Brother Fell, written in elegy of his friend and fellow Black gay poet Joseph Beam, Hemphill writes, “When my brother fell/I picked up his weapons…a needle and thread/were not among/his things/ I found.” Elsewhere in the poem, Hemphill cautions against the dangers of premature memorializing. “It’s too soon/to make monuments/for all we are losing.” I found these lines once again in a beautiful newsletter published yesterday by the writer E.Y. Washington, who uses Hemphill’s words as a guide to remind us of the political responsibilities and legacies that queerness holds.

As someone who considers myself in study and practice of memory work, as someone who believes that craft (and specifically textiles) can play a beneficial role in political movements, these lines challenged and unsettled me. This poem was originally published in the 1992 collection Ceremonies, five years after the 50,000-panel AIDS Memorial Quilt was unveiled on the National Mall. When I read Hemphill’s words that positioned the needle and thread outside the realm of resistive political tools, I felt momentarily surprised. At the same time, I instinctively understood the frustration that radiated from the poem, written in the context of a mainstream AIDS movement that sidelined the voices of Black activists and increasingly centered whiteness and respectability, displaying what Hemphill calls “the lack of truth/the absence of willful change/and strategic coalitions.” It can be hard to appreciate the symbolic when an entire generation of your friends and peers are dying around you, when every intimate encounter has become a minefield and the medical system has already counted you among the deceased. “I realize sewing quilts/will not bring you back/nor save us,” Hemphill writes to Beam.

Similarly, I’ve been meditating on Hemphill’s insistence that “It’s too soon/to make monuments.” There is a way that monument-making consigns its subjects to the past. Taking time to grieve the lives lost and document their existence is crucial work; enforced forgetting is one of the many tools used to keep oppressed people disconnected from a knowledge of their history and political agency. Hemphill’s words, however, force us to confront the ways that memorialization can also be used in service of complacency. Monuments can so easily be integrated into national narratives of pious and depoliticized mourning. “As beautiful as it seems, memorialization can’t save the living or bring back the dead. Fighting, at least, ensures the former,” Washington adds.

Washington and Hemphill also led me to reflect on my work growing plants and saving ancestral seeds. I see this fundamentally as storytelling work, learning and weaving together embodied histories of imperialism, ecological change, food, and so much more. Washington and Hemphill remind me that while this work is always in honor of the dead, it is also in responsibility to the living. I don’t have any easy answers to the contradictions these two raise, and I think that’s part of what makes their words so instructive. In order to do the work of craft or storytelling or memory-keeping with integrity, I believe—and I am being taught—that it’s necessary to reckon with the limitations of these forms. I hope to stay in this space of discomfort, this commitment to finding the tools that are most effective for the moment. I want to remember the perils of romanticization, the ways that we can sometimes turn towards the past in order to avert our gaze from the present. What are all your memorials in service to? I hear Hemphill asking. What weapons are you gathering from the belongings of the ancestors, and how are you carrying them forward?

From the nursery: