bong trees and runcible spoons

on the owl and the pussycat

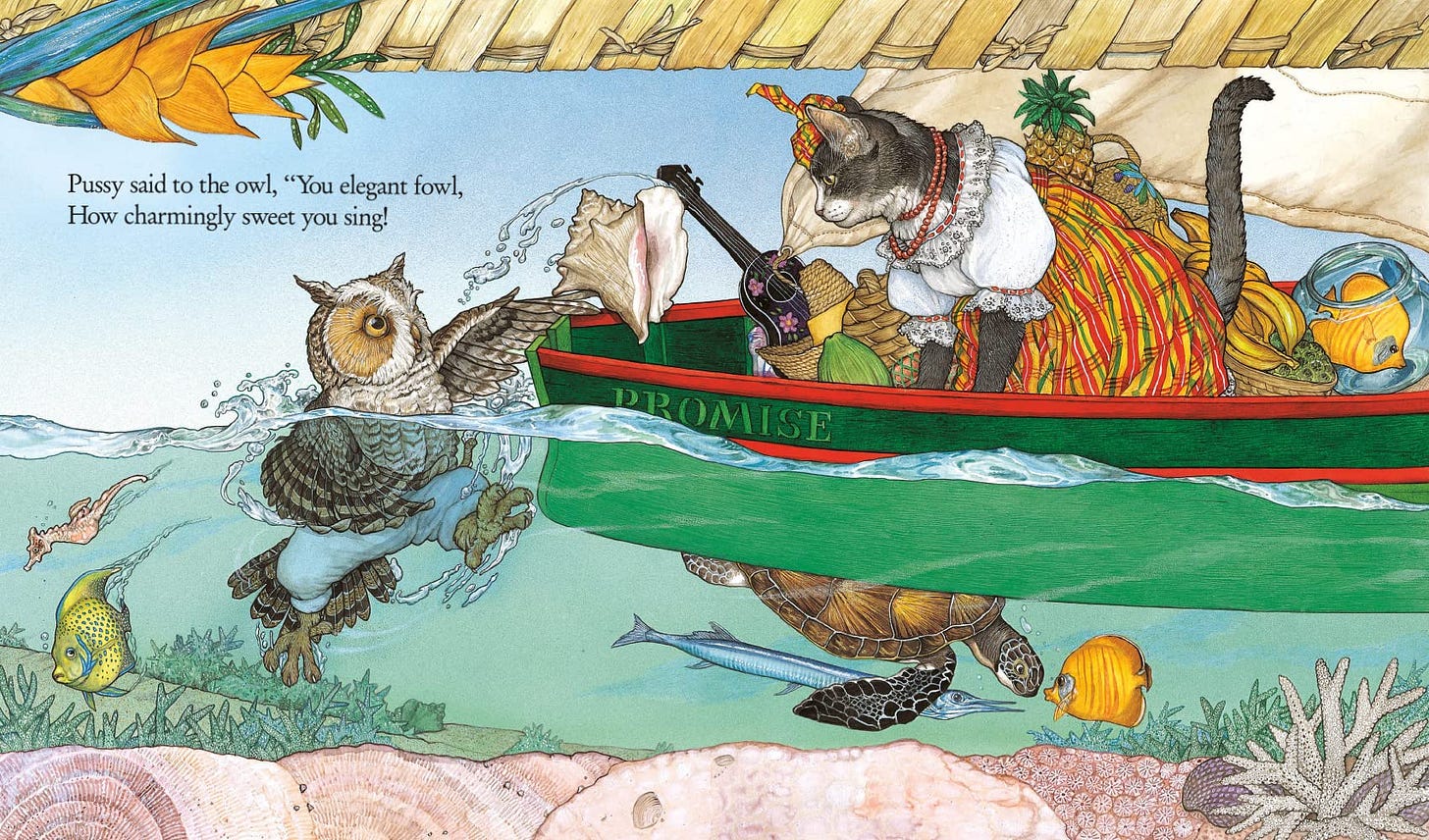

At a recent trip to the Fabric Workshop and Museum, I spotted an Owl and Pussycat doll made by artist Kiki Smith. The grim-faced duo brought back memories of one of my favorite books growing up—Edward Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat. The rhyming tale follows the love story of its titular protagonists as they make eyes at each other, obtain a ring, and sail to get married in “the land where the bong tree grows.” The combination of fanciful iambic meter and Jan Brett’s lavish illustrations still have the enormously pleasing effect on my brain that they did so many years ago. I bought a copy this week, and seeing my old friends in their tropical haunts made me curious about the book’s origins. Was a bong tree a real thing? Where was this story supposed to take place? (Brett’s illustrations were described by Booklist as a “brilliantly lit Caribbean landscape.”) Whose mind dreamed up the absurdly accurate nonsense phrase “runcible spoon”?

It turns out a bong tree is indeed a real plant. Nothaphoebe umbelliflora is indigenous to Southeast Asia, where its bark has been used to make incense sticks, adhesive agents, and building materials. The book’s idyllic setting isn’t technically a real place, but definitely influenced by its author’s travels and a healthy dose of Victorian Orientalism. Edward Lear was born in 1812 in London, and became a celebrated zoological artist in his teens. He was disabled since childhood, experienced persistent “melancholia” along with abuse and instability, and had numerous and well-documented infatuations, love affairs, and unrequited passions for other men. An outcast in British society, he spent most of his life traveling to places like Italy, Egypt, India, and Sri Lanka. In an extensive review of a recent Edward Lear biography, Adam Gopnik points out that many Victorian men of Lear’s position found sexual freedom “abroad” that was unavailable to them in their home country. It’s hard not to see the irony in white Englishmen making self-liberatory travels through the colonized world. During Lear’s lifetime, England drastically expanded its brutal colonial regimes, becoming the largest imperial power on the globe.

When Lear first published The Owl and the Pussycat, his colonial readers may have seen the bird and cat duo as representations of any other respectable British travelers. In search of adventure and romance, they sail away to the tropics. They take plenty of money with them. In the absence of a wedding ring, they use their purchasing power to separate a certain pig from his nose ring. But I love them too much to believe all of that, and besides, Lear has new readers now. Leaning into the linguistic pleasures of the book this morning, I chased other, more speculative ones. I wondered instead about a story in which the lovers only go sailing because they want to, and not because they’re Getting Away. What if the lovers are already from a tropical island, and are simply journeying a little further, or visiting one of their island birthplaces, and perhaps they have a deep and well established friendship with the fellow who gives them the ring?

Gopnik writes that for Lear, The Owl and the Pussycat “was a dream of a love he had never enjoyed, helped along by a well-wishing community.” As we know, dreams birthed from empire can only take us so far. I have great affection for this plumed and furry pair, and my lifelong readerly love now pulls me towards a joyful rewriting. How would this story feel if the bong tree were not a strange attraction for the couple but a familiar and comforting presence of the landscape? What would it look like to recast this story, to pry apart the silences in its extravagant rhymes and recast it as a queer and oceanic, abundant and inherently tropical love? I’m working on it—in the meantime, I made you a playlist with three hours of music based on the owl and the pussycat, from classical opera to Kidzone to a Taiwanese TV drama soundtrack song. You’re welcome.

WRITING:

I published two pieces near the end of 2021 that I’m quite proud of, and I realize I haven’t shared them here. I wrote about the Flatbush African Burial Ground for Urban Omnibus, and interviewed vintage curator Keesean Moore for Architectural Digest.

READING:

Voodoo Hypothesis by Canisia Lubrin

Rifqa by Mohammed El-Kurd

Alicia Kennedy on the history and future of the sugarcane industry

How the “pandemic-fueled land rush” has worsened farmland inequalities

LOOKING AT:

Every quilt Rosie Lee Tompkin ever made.

If you can, please consider signing up for the paid option of this newsletter to support me bringing interviews, articles, and stories to your inbox every other week.